Better Homes Than Gardens

Kingston Gallery, Boston, MA, August 30th–October 1, 2023.

“Going Going Gone” 2023. LED sign and vinyl on corrugated plastic. Approximately 8’ x 16’. Photo by R. Leopoldina Torres.

1994, Dad and I:

“Please, don’t mow the flowers.”

“Those aren’t flowers, they’re dandelions. They’re weeds”

“What’s a weed?”

“It is a plant that you don’t want growing?”

1995, Mom and I:

"Where is Grandma from?"

"Ireland, it's across the sea."

"Why did she leave?"

"I don't know. Sometimes it's just too hard to stay."

1996, Mom and I:

“That magazine, Better Homes Than Gardens, is pretty. I wish our house looked like that.”

“It’s Better Homes AND Gardens, and that magazine is for rich people.”

2007, Dad and I:

“The town put a line on our house and we don’t have the money to pay for the debts—

I don’t know what we are going to do!”

“Are we going to lose the house?”

“I’m praying to God that we don’t!”

2023, Anonymous Person and I:

"I need to go home early— they're building this huge apartment building where I live and we are fighting against it. It's so out of character with the neighborhood."

These recollections are personal experiences and observations about the concept of home. Beyond the physical structure, I challenge the economic, societal, and governmental institutions that make securing a safe home and community (aka the American Dream) a Sisyphean feat. This work titled Better Homes Than Gardens, is autobiographical and holds a mirror to what many Americans may not want to admit—complicity in the nationwide housing crisis.

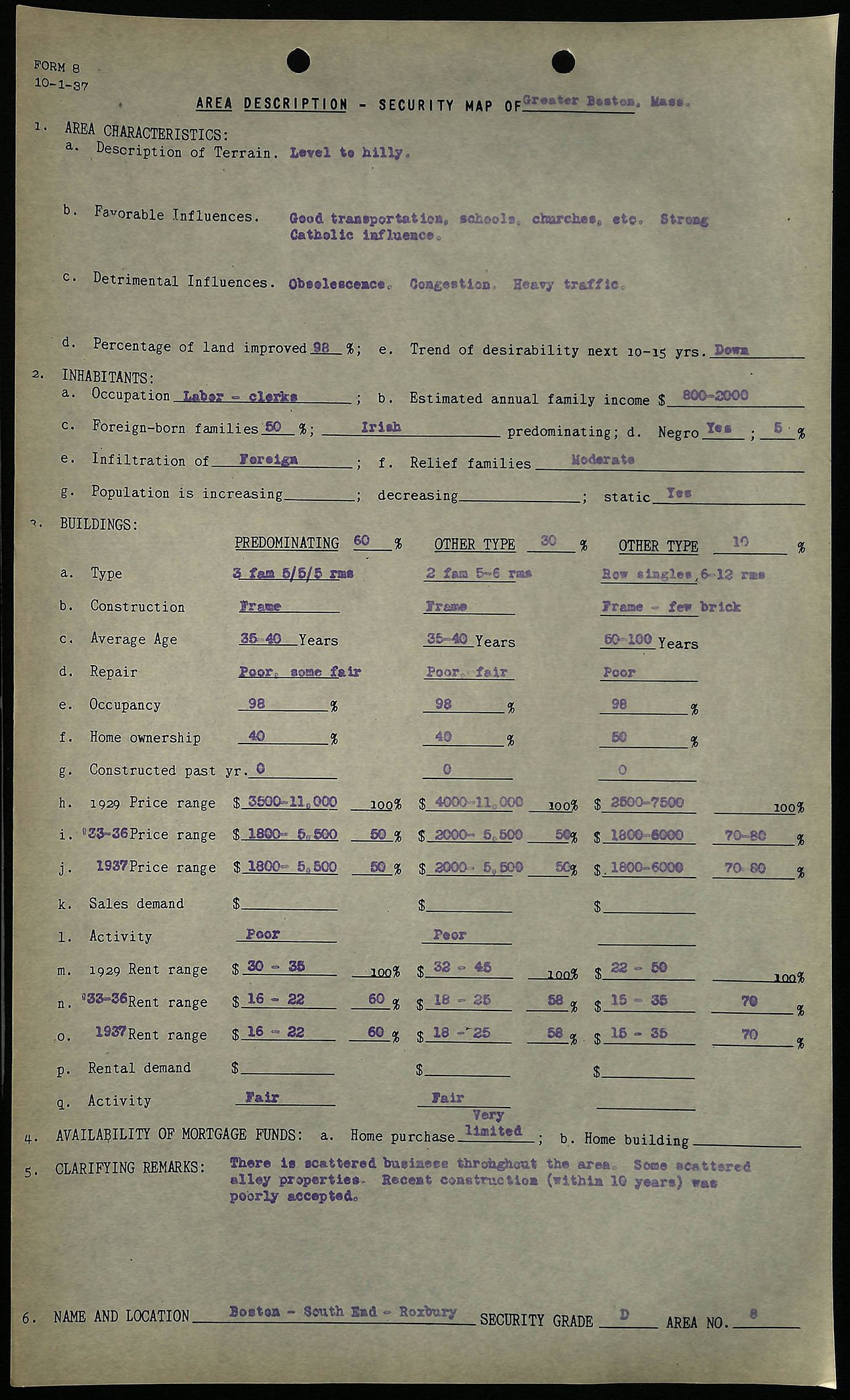

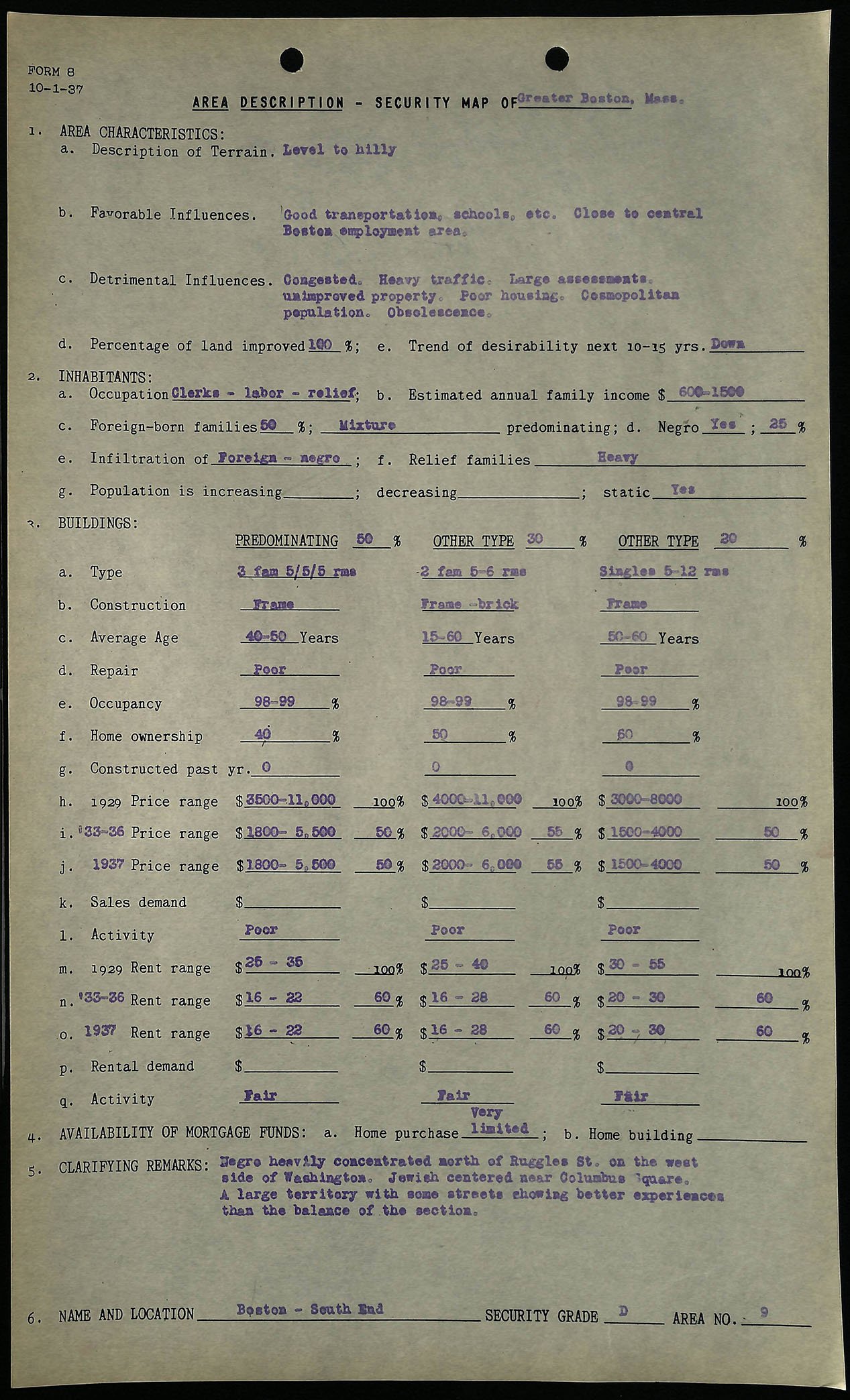

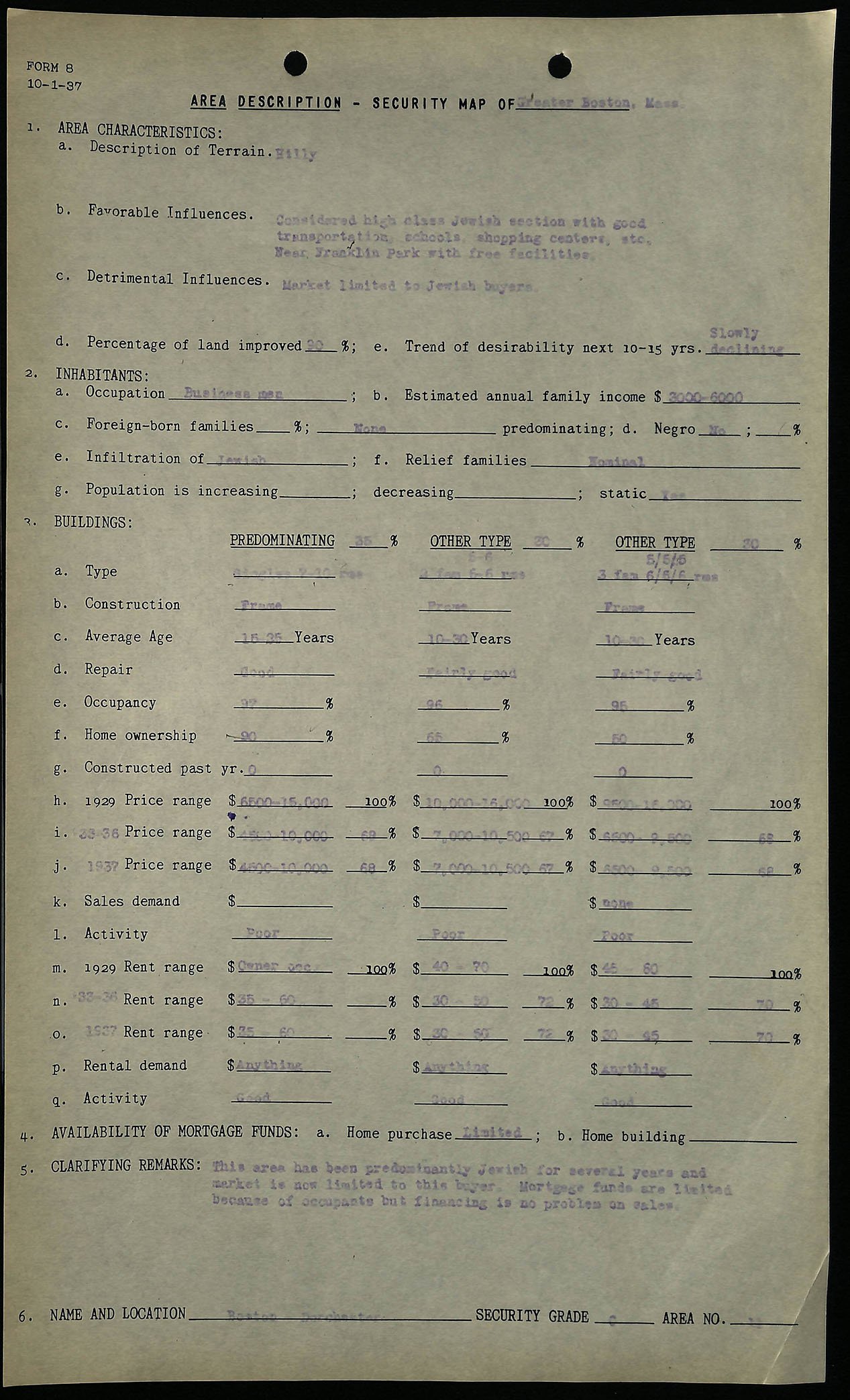

In 1938, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created to expand homeownership under the New Deal. Its function was to assess the mortgage-lending risk within the neighborhoods of major cities and create color-coded maps based on who made up the households. Racial, ethnic, and economic diversity was a cause for demerits on HOLC maps, with communities of Black people, Jewish people, and immigrants described as an “infiltration” or “encroachment.” Thus, the creation of redlined cities kept economic and racial segregation to this day.

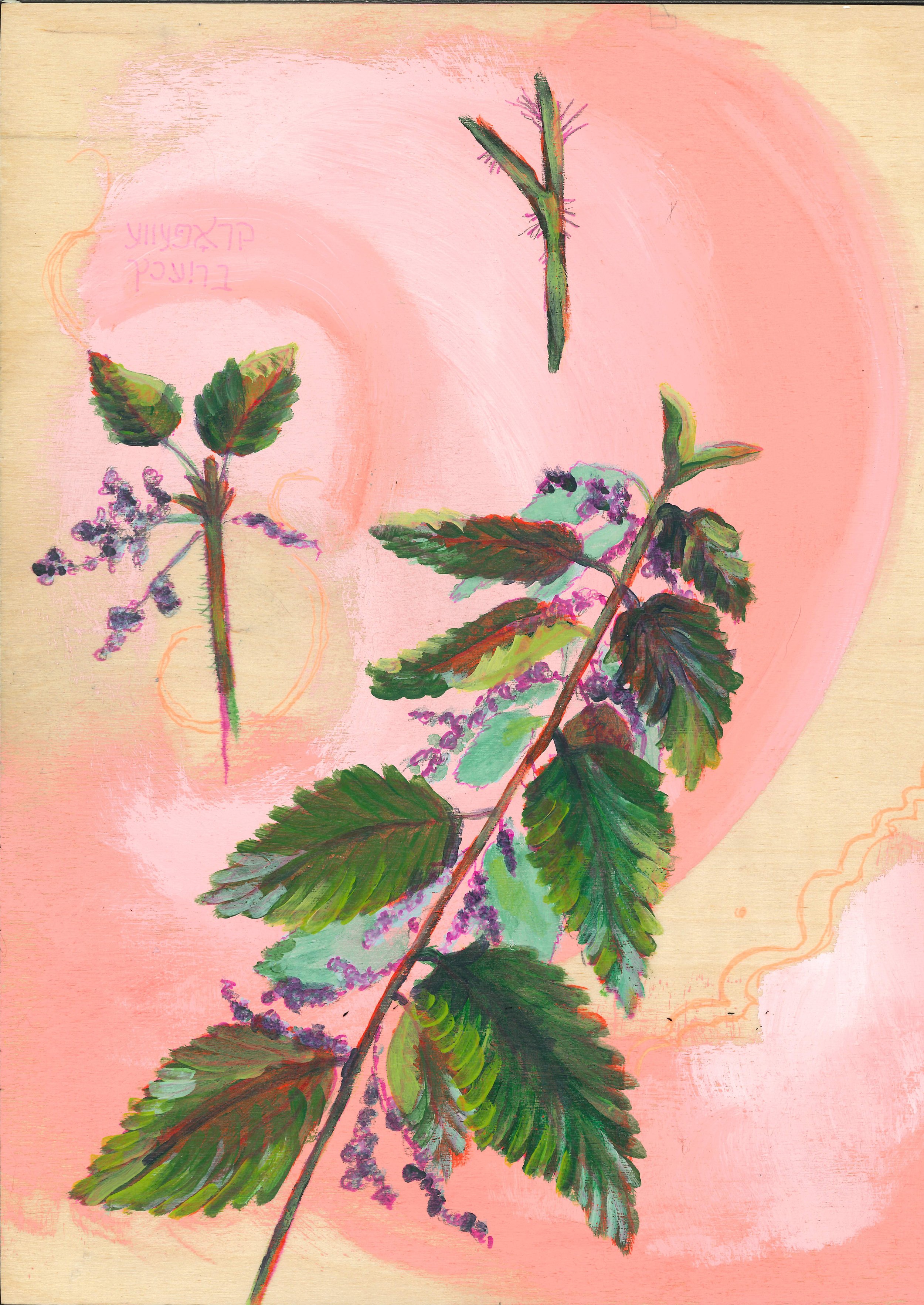

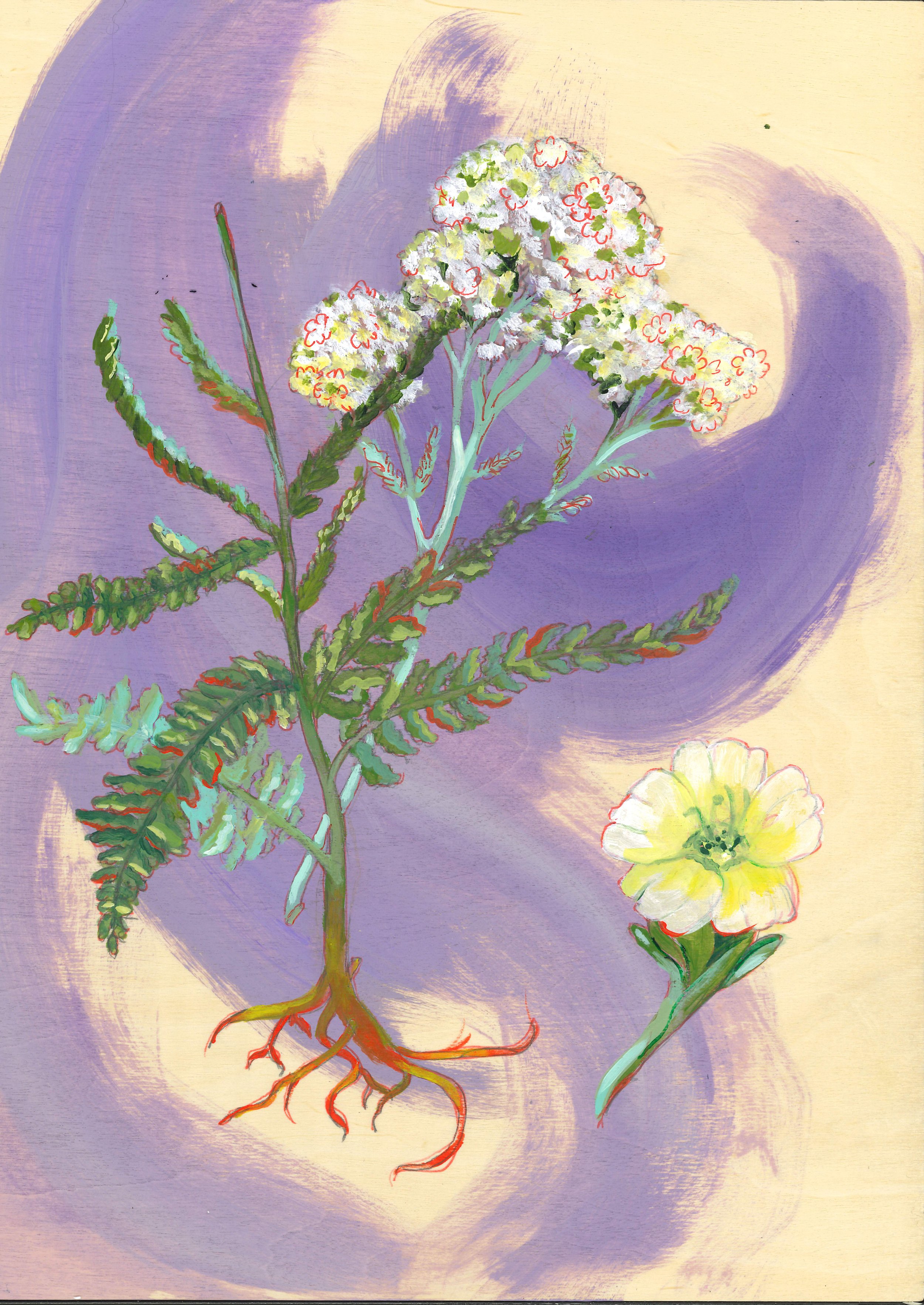

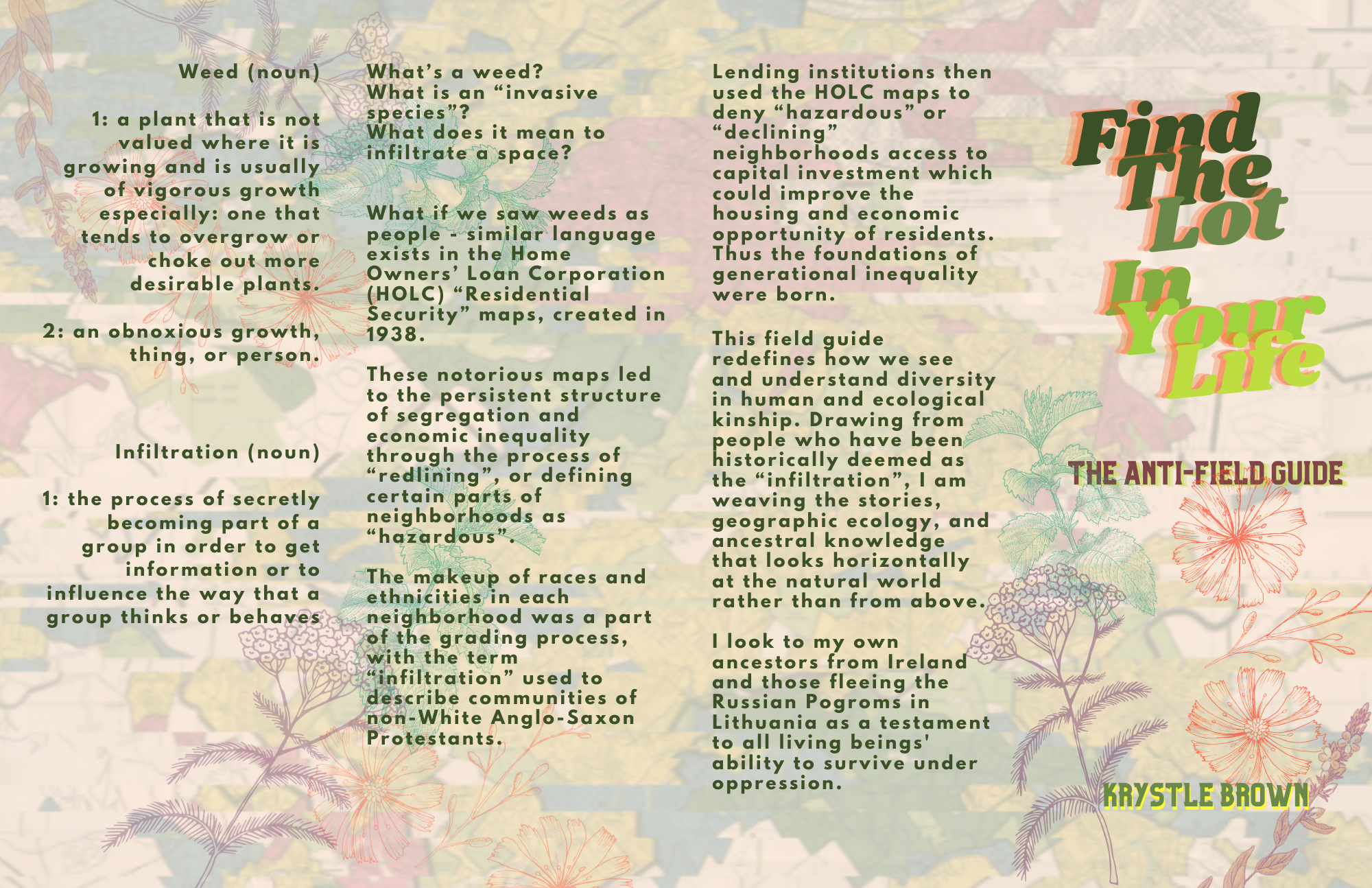

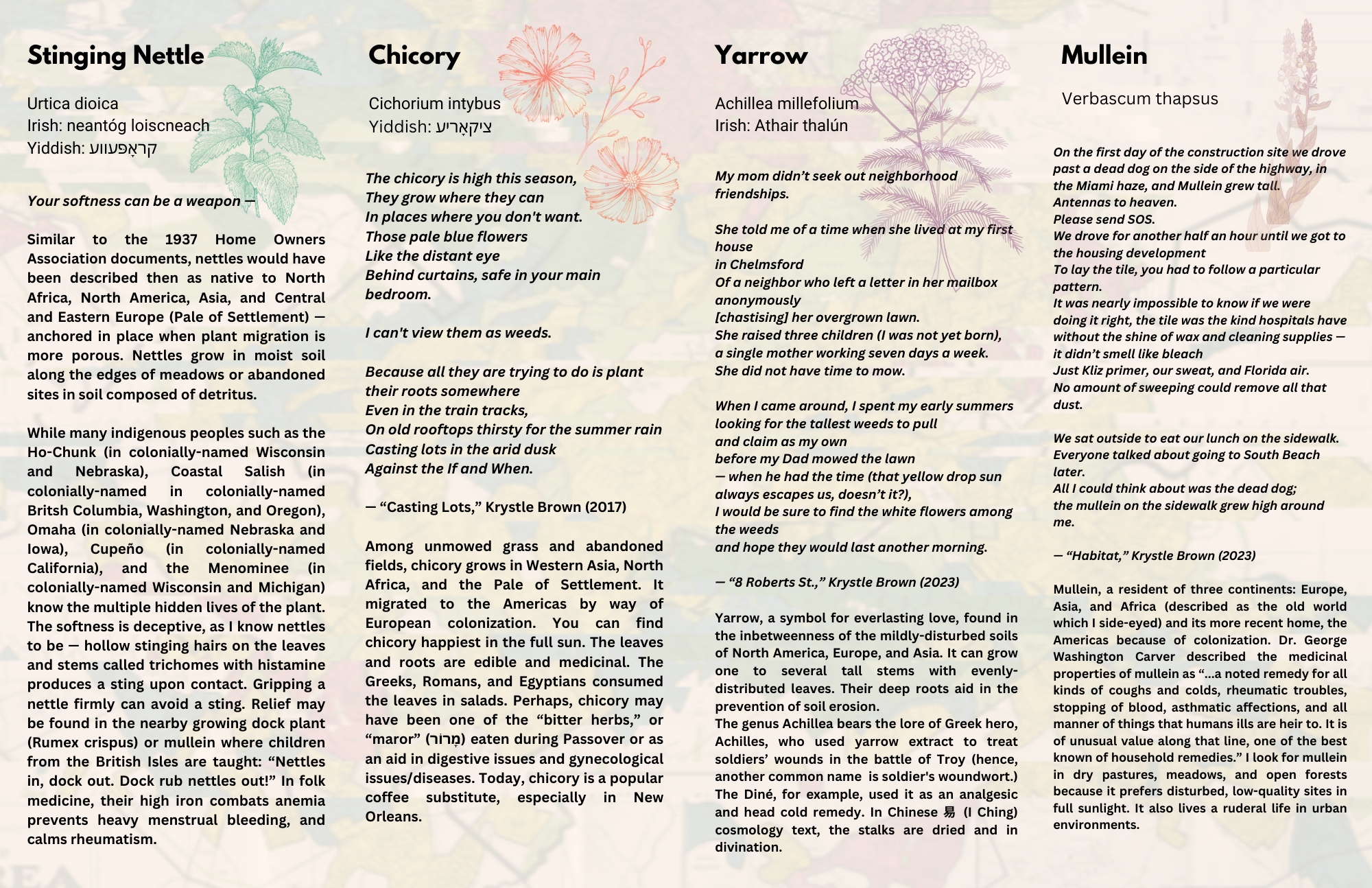

An early memory I have of my father mowing the lawn, cutting down the flowering ‘weeds’ that flourished in our yard, made me rethink how we categorize living beings. A ‘weed’ is considered undesirable in a particular situation, growing where it is unwanted. The in the installation, Find Your Lot in Life, are all edible and medicinal, with rich histories in Black folk medicine, Indigenous American cultures, and my ancestors in Ireland and the Pale of Settlement. These plants grow in inhospitable soil and environments, they give nutrients back to the earth. What can we learn from our treatment of these plants and the natural world?

After my parents passed away in 2017, I looked at the house we lived in: it was dirty and nearly uninhabitable. By taking from my family’s lived experiences and what I have realized about my home, neighborhood, city, and country, I am left with uncomfortable observations about the human condition. We were always one bad day away from losing our home.

Since then, I have developed a concept-driven practice incorporating painting, photography, and installation. In this work, I warp Cash for Houses scam signs and create moments of whimsy with nostalgic neon signs and custom View-Master toys to subvert the notion of shared prosperity. There is a hauntological underpinning coursing through my process: What future can we arrive at if we are still living within the specters of the past?

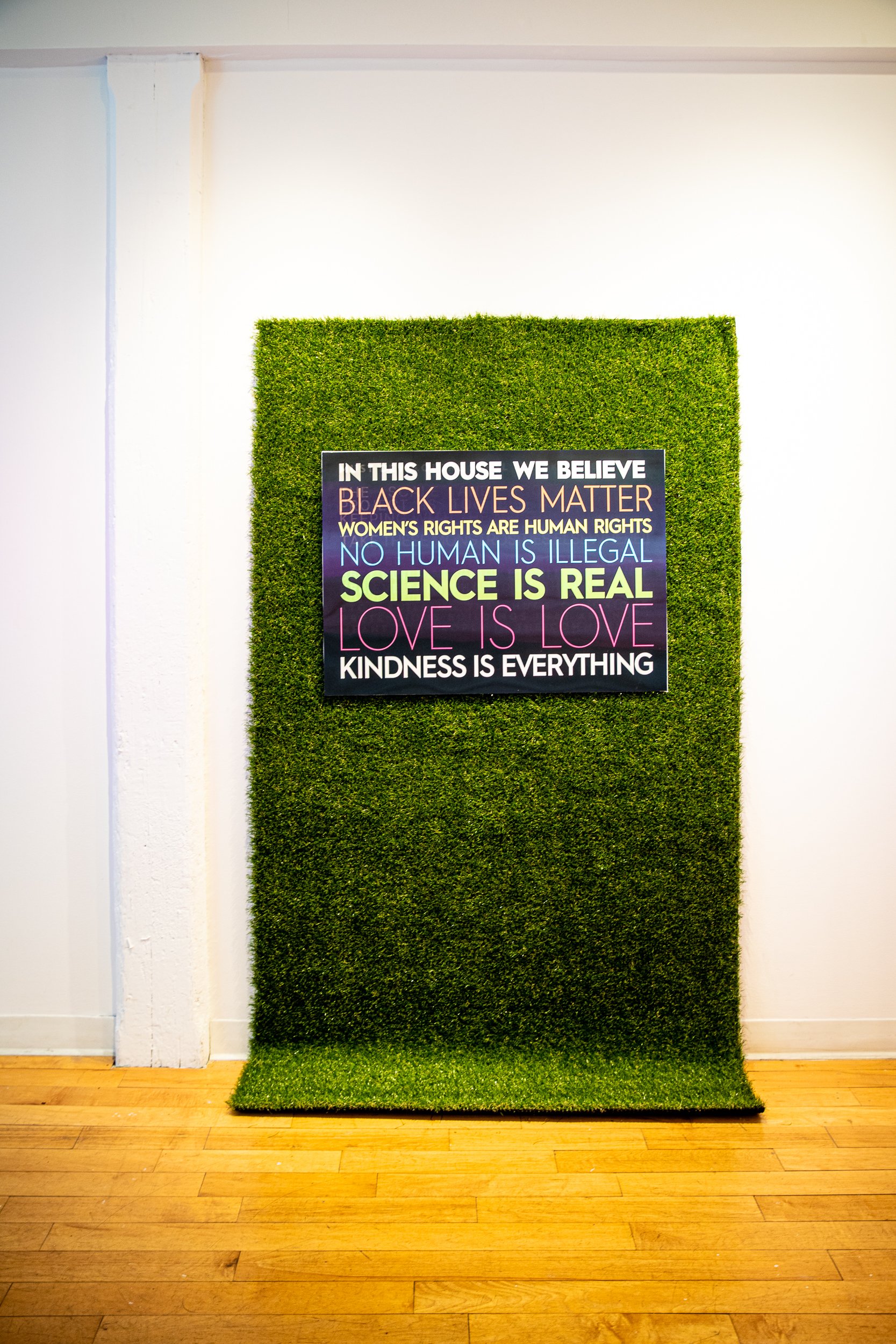

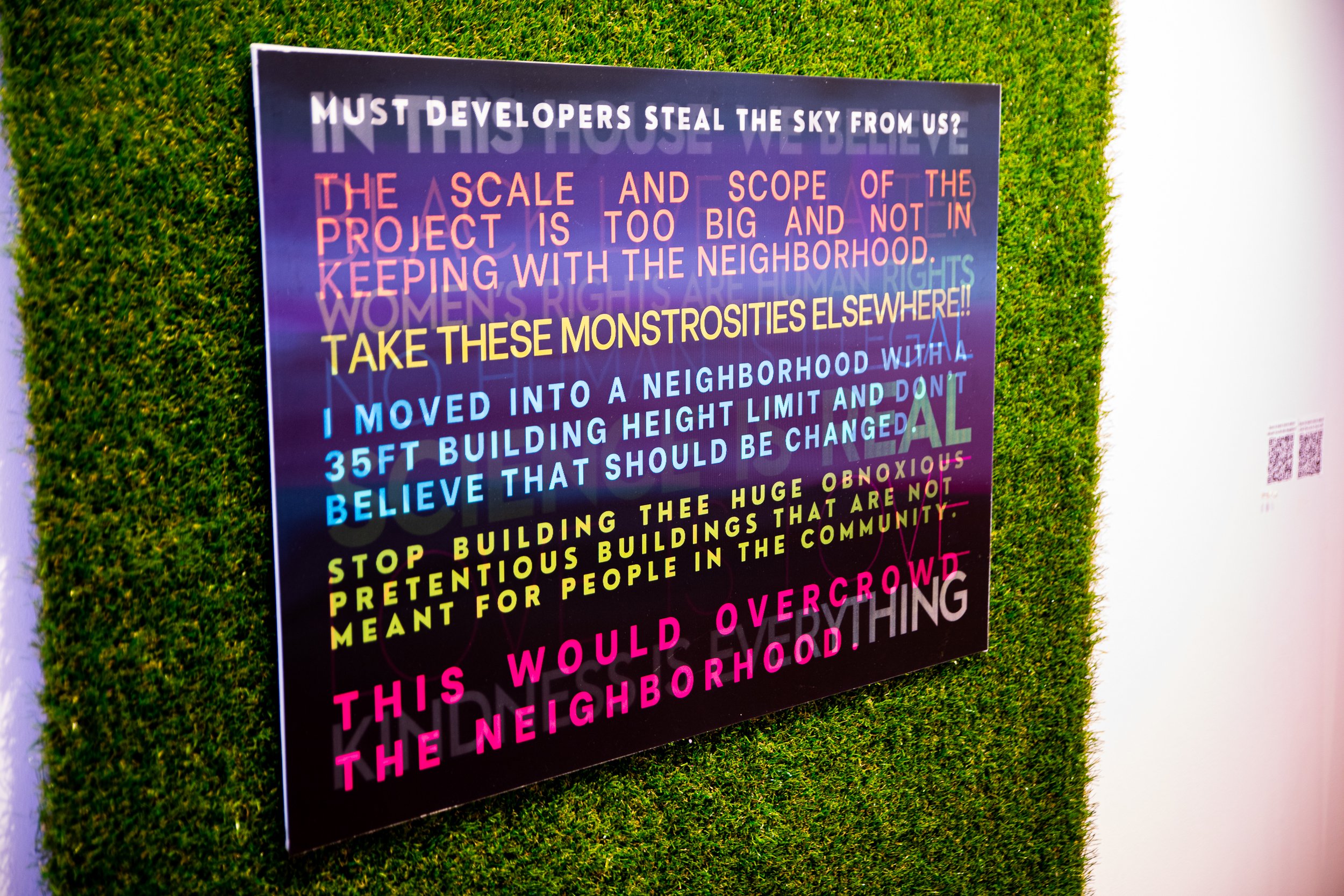

Most people who view this work ask, how can I help? The housing crisis and widening wealth gap are undeniable, and its effects are everywhere. The lenticular sign Would You Be My Neighbor? uses popular lawn signage of liberal homes and exposes the darker underbelly, with written responses from Boston residents against housing developments, from East Boston to West Roxbury. The lawn behind the sign is fake, echoing the virtue signaling that “In this house, we believe…” signs signify. It seems as though marginalized people’s safety, comfort, and well-being only matter when they are not inconveniencing those who are already secure.

About the individual works

Going Going Gone

Call 800-339-7368

I promise you will not be on a spam call list.

Rather, you will be connected to the Invitation Homes Headquarters, which is the largest landlord of single-family houses in the U.S. and is a subsidiary of the 434 billion-dollar company (as of December 2017), The Blackstone Group. It primarily operates in the Western states and Sun Belt, managing 82,000 properties, most of them starter homes that are three- and four-bedroom houses.

In September 2021, investor companies bought 29 percent of the homes sold that were in the bottom third by metro area sales price, compared with 23 percent of homes sold in the top third, thus reducing the already limited supply of available and affordable homes to families. Investor-owned homes are typically converted from owner-occupied units to rentals or upgraded for resale at a higher price point. Meanwhile, Invitation Homes has proven to run exploitative housing situations, from hazards like broken heating systems and mold to untenable rent increases. It is no accident that corporate landlords have increased in places like the West, Mid-West, and South, where renter rights are less robust than those in the Northeast.

How and where are housing investors purchasing these homes to rent or sell at a profit? There is a strategy that they use to target potential purchases. Homes that are in disrepair or have high tax liens make for particularly appealing investments. Areas that have been hit by natural disasters or have large concentrations of homeowners with a lot of equity are carpeted with robust advertising, such as corrugated plastic signs in bright colors to command attention, found on lawns and telephone poles. Companies will also target families that have recently experienced divorce or death, found through public records, with cold-calling and unsolicited postcards to help them out of their desperate situations with cash for their homes. Using deception and scare tactics, HomeVestors, a US real estate investing franchisor, will target the elderly, infirm, and those close to poverty. Often, these are homes occupied by elderly folks who may be making the transition to assisted living.

From selling to buying or renting, immigrant, BIPOC, and low-income folks are particularly vulnerable to corporate landlords and housing investors because they tend to have far less wealth than their affluent, white counterparts. For example, in the Boston area, close to 80% of white adults own a home, whereas only one-third of U.S. Black adults, less than one-fifth of Dominicans and Puerto Ricans, and only half of Caribbean Black adults are homeowners. The wealth gap in Boston between white households and Black households is extreme; white households have a median wealth of $247,500, Dominicans and U.S. blacks have a median wealth of close to zero. Owning a home is one of the ways to ensure generational wealth. Without easy access to home ownership, the wealth disparity between homeowners and those without homes will continue to increase.

I began seeing these signs myself around Lowell several years ago, before my parents passed away in 2017. Though companies like HomeVestors and InvitationHomes have not gripped into places like the greater Boston area as the rest of the country, the ubiquitous (and ominous) “WE BUY HOUSES FOR CASH” signs unceremoniously slapped on light poles always loomed as a specter of the 2008 housing crash. I cannot help but think of when I nearly lost my own home in 2007 (not due to the recession) and the fear of where my animals will go, how will I go through college, and what will I do. To this day, I hold on to the prevailing anxiety of affording the home I now own. What if disaster strikes again? Will I be ready?

In 2017, after my father suddenly passed away, my mother sold our home to a house flipper for around $150,000. Most of that money went to the unpaid mortgage, and what was left over went to the apartment she secured down the street. Seven weeks after my father’s death, my mother passed away as well, and my siblings and I split the remaining money she had from the house. I don’t remember all the details, to be honest. The late summer and autumn of that year feel like a hum.

That was the end of generational wealth. I am still luckier than most.